Fig. 3. Patty Chang - Doll, 2001

Fig. 4. Vanessa Beecroft - VB45.900.ali, 2001

Fig. 5. Tanja Ostojic - After Courbet, L´origin du Monde, 2004

Fig. 6. Marlene Dumas - Skaam, 2009

Pudenda Agenda by

Jerry SaltzVagina envy. Everybody knows it's as prevalent as penis envy and probably more intrinsic, given that the mother of all envies may be caused by the inability to give birth. To settle a wager about which gender has better sex, Zeus and Hera asked Tiresias, who for reasons I won't go into here had spent seven years as a woman. When he chose women by a ratio of nine to one, Hera was so enraged she struck him blind. Zeus took pity and gave him the gifts of prophecy and long life, and the rest - as we know - is Oedipus.

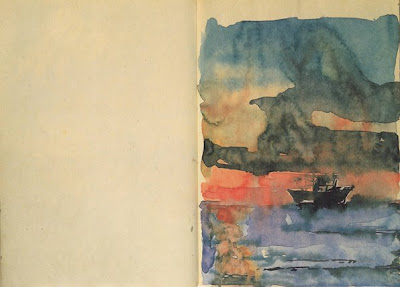

Nowadays vagina envy has been joined by pudenda power. One famous expression of it is Courbet's 1866 spread-eagle crotch shot,

The Origin of the World, which scandalized not only because it displayed a flash of pink, but because it portrayed the female sex in its full hairy glory, rather than classicized and bare. Then there's real life: John Ruskin, who on his wedding night fled at the sight of his wife's pubic hair. This was before photography (and Courbet's painting), and the only female nudes he'd seen had been in art, and carefully tonsured. He thought his wife was grossly deformed, a freak.

Today, Ruskin might have been much more at ease, and Courbet's canvas might be viewed as unkempt. After all, we live in the age of Xtreme grooming, and it's been pioneered by women. Or I think it has. As a straight male art critic, I may not be qualified to say much on the subject, but it's become all but unavoidable. From private parts on figures in the work of Tracey Emin, Su-en Wong, Sarah Lucas and Marlene McCarty to those in the photographs and self-portraits of Patti Chang, Malerie Marder, Katy Grannan, Kembra Pfahler and Vanessa Beecroft, hairless pudenda are popping up in art galleries all over town.

The shaved, waxed, trimmed and otherwise depilated female pubis that has become a cultural norm might be called a Pandora's box of conflicting fears and desires. On the one hand, there's the fear of hair or chaetophobia. Hair is a sign of maturity and strength, which far too many men find scary in women. Removing pubic hair may be a wish to infantilize women - to make them look more like little girls. Which, if taken further, comes uncomfortably close to pedophilia.

For their part, women may internalize a distaste for hair and develop a love of bareness. Some would say this is self-exploitation. But it seems to me - and I'm sure I'm not alone - that women are turning something that objectifies them into a tool of empowerment. This is consistent with lowered waistlines and bared midriffs, which may be surrogates and pointers for the pudenda below. A woman I know describes the bared-belly look as "a way of showing more skin without revealing more breast or being tacky." Either way, visibility is power. The male anatomy has already taught us as much.

But in fact what we're learning is ancient wisdom. Women's vulvae have been represented both accurately and abstractly in Eastern art for centuries, especially Indian art. Think of the carved stone yonis or the illuminated manuscripts depicting couples in flagrante delicto. There may be more images like this in Western art than we know about, but recent exposures have made me see Georgia O'Keeffe's work, for example, in a more explicit light. I always thought of O'Keeffe's undulating landscapes as genital-like, but thinking of them as hairless anatomy is really tantalizing.

Kembra Pfahler, the former lead singer of the notorious cult performance group the Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, explained her shaved privates by saying, "I do it because it looks good. Which," she added, "is my basic motivation for everything."

On the night of her opening, a few weeks back, as a crowd pressed close to a makeshift stage at American Fine Art at PHAG, that motivation was on vivid display. Pfahler and the seven members of her band arrived at the gallery wearing only black wigs, body paint and boots, flaunting their bare yonis like crazy.

Striding to the stage, they performed the circus-meets-de Sade "Wall of Vagina," which culminated in all but one of the group lying facedown, in a stack, butts toward the audience, legs spread. The remaining member squirted white liquid from a turkey baster into this seven-layered crack, from the top down. It was an outrageous money shot à la Julia Child - one that evoked the Vienna actionists, Annie Sprinkle, Jack Smith, Leigh Bowery and Carolee Schneemann. The group then stood up, walked out and disappeared naked down 22nd Street.

Things are a bit drier at Deitch Projects (18 Wooster Street), where Vanessa Beecroft is once more proffering an irksomely shallow yet strangely illuminating mirror, reflecting her narcissism, our voyeurism and the world's fixation on the female form. This time she's doing it with enormous, history-painting-sized color photographs of her signature naked-lady-as-mannequin performances.

The latest images show groups of more than a dozen models, all white in one performance, and all black in the other. With a noticeable difference: The white models are completely nude and waxed, while the black models wear strip-like bikinis. Interestingly, they all wear full-body makeup and high heels, as if an unaccessorized woman is still off-limits.

Beecroft's regimented models, and her predilection for beautiful, blond Aryans, have always made us think beyond the nude, to type; now she introduces race. But with the black women clad, the suggestion is that we're not ready to handle this particular truth - which is that the power of the shaved pudenda increases in direct proportion to the "otherness" of the woman in question. Or does it? After all, the more you see of the female anatomy, the less "difference," "otherness," or "mystery" you can project on it. When difference is accented, it is sometimes reduced.

When it comes to nudity, women have always been in the artistic vanguard, whether they liked it or not. The female body has been presented much more naked, much more often than the male body. It's anyone's guess what could happen next. But if men follow in these footsteps it could lead to our particular last frontier: the visible hard-on.'

NB Jerry Saltz is art critic for the Village Voice, where this review first appeared.